By the Rev. Ted Foley, Deacon

Christ Episcopal Church, Toms River, NJ

Jesus said, “If you were blind, you would not have sin. But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.” (John 9:41)

Chapter 9 of the Gospel of John tells the story of the healing of a man born blind and how the Pharisees refused to believe this amazing miracle performed by Jesus. The Pharisees refused to open their hearts and minds and they remained cut off from the saving grace that stood before them. At the conclusion of the story, Jesus admonishes them and their willful blindness – “But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.”

The relationship between the Pharisees and the man born blind was broken. And Jesus’ admonishment reminds us that the first step in reconciling broken relationships is to get rid of any blindness that we may have and admit to our sinfulness.

In the year since the murder of George Floyd, much has been said about the need for reconciliation between white people and people of color. As a white person, I sometimes wonder whether we are ready to take that important first step towards reconciliation – admitting our blindness to our own complicity in the racial dynamics that are at work in our country?

As part of my church ministry, I have had the opportunity to participate in several trainings and discussions involving racism in the United States. Much of the discussion focuses on the racial disparities resulting from the policies, laws, and practices of institutions that oppress people of color. Often the information is new to the white participants who are horrified by how people of color continue to be oppressed in this country more than 150 years after the abolition of slavery.

Invariably, these trainings pivot to the subject of “white privilege,” and at this point, the discussion can become heated. White privilege is the flip side of the coin of racism. White privilege is not so much about how people of color are oppressed by racism but how white people are advantaged by these same practices. The topic of white privilege is sensitive. Often, the mention of “white privilege” triggers reactions of anger and resentment among the white participants. I am familiar with these feelings since I too had this same reaction upon first hearing the term. (Many of you reading this may be having this same reaction right now.)

Usually, white people resist the idea of white privilege saying things like, “My grandparents came to this country with nothing. They had to work for everything they achieved.” Sometimes the participants talk about themselves and how hard they have worked to get to where they are. That was my reaction. I did not come from a family privilege. I had to work hard all my life.

I was raised in a blue-collar family where my parents often needed financial help from my grandmother just to get by with the basics of life. And growing up, I aspired to attend college but knew that I would need to pay my own way.

So, but the time I was 12, I worked at jobs that often required hard labor since these were the highest paying. In my high school years, I worked weekends and summers as a caddy at a local private golf club. During my college years I worked as a construction laborer. These were hard backbreaking jobs but paid well – so well that I was able to pay all my college expenses and even had funds left over for my wife and me to buy a house early in our marriage.

After college, the hard work continued. Our first house was distressed but we refurbished it with sweat equity and doubled our money in five years. We repeated this process a few more times and built a substantial nest egg. All of this required hard work – work that I had been doing since the age of 12. So, you can understand my reaction to the discussion of white privilege. From my standpoint, my achievements were the result of hard work. I really did not see any privilege in my situation.

However, after hearing the stories of people of color and comparing them to my own, my eyes were beginning to open. I began to see how white privilege was at work in my life. I began to see how I was given opportunities that were often denied people of color. I began to see how I benefit from the institutional racism that oppresses others.

As the fog of my blindness slowly lifted, I saw how I always worked in a “white” world. Even though I caddied in an area surrounded by African American neighborhoods, not one Black person was allowed to work at the same club where I could. In construction, I worked on several sites in predominantly Black neighborhoods. However, the construction crew was always all white, so I got the job. Regarding my housing investments – all the profits I made were from real estate sales in all white areas where housing prices grew. This would not have been the case if my property had been hamstrung by the legacy of Red Lining and other discriminatory practices.

Like most white Americans, I lived in a fantasy world of thinking I am a self-made man. I was blinded to the fact that, despite coming from a poor family, I still enjoyed many opportunities just because I was white. I now see that, no matter how hard people of color work, they are often blocked out of the same kind of opportunities. I eventually saw – and now confess – that my white privilege gave me exclusive opportunities that contributed greatly to my success. My blindness was lifting but that is only the beginning. More needs to be done.

I suspect that my story is not unique. While institutional/systemic racism exists across society, most white people are blind to it – in the same way that I was blind to it for decades. However, there are steps that each of us can take to heal this blindness. There is Anti-racism training that is offered several times a year in our diocese. Also, the Episcopal Church offers a program called “Sacred Ground” that could be sponsored by your parish. And there would be value in participating in a discussion group using one of the many good books on racism that have been recently published.

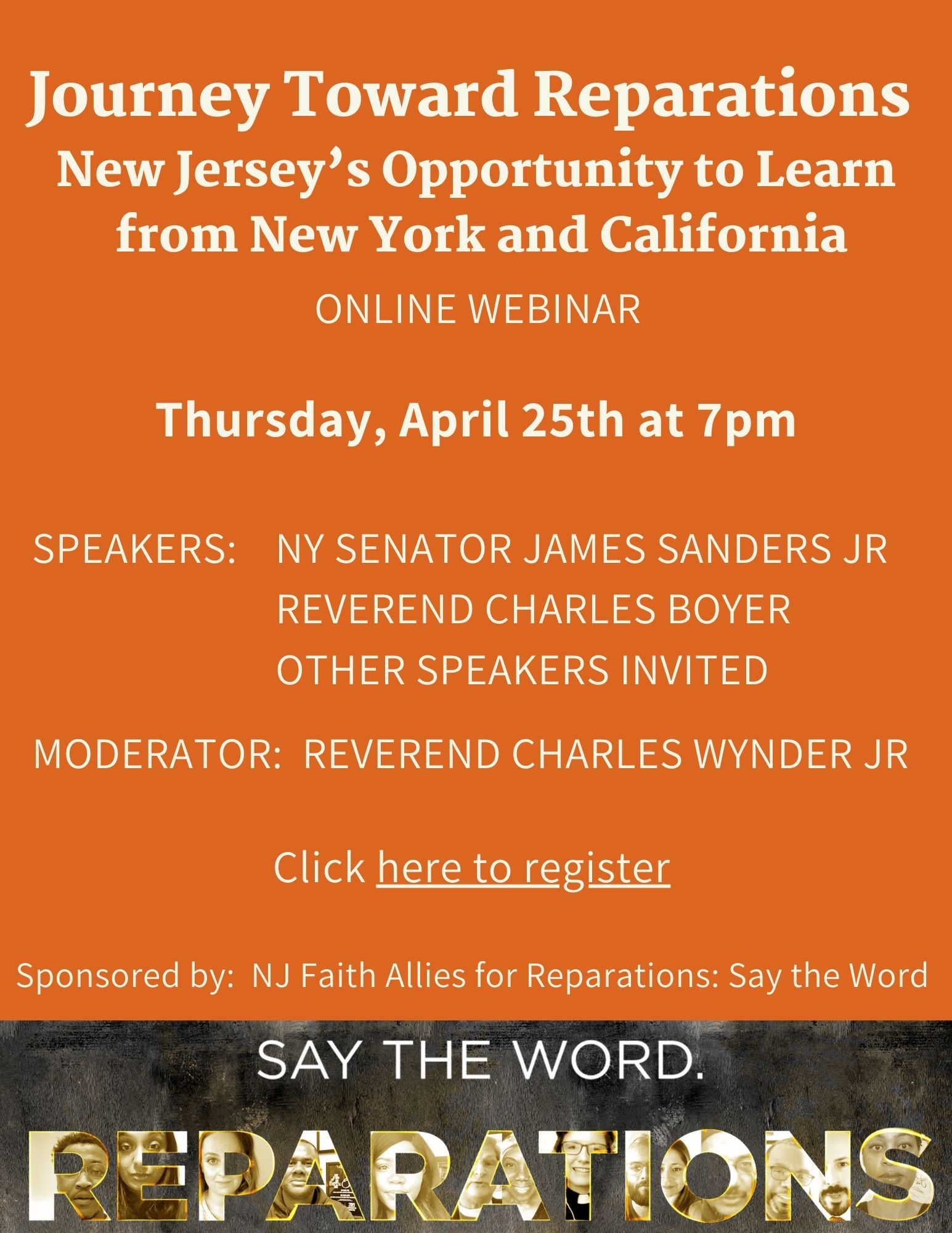

There is also the possibility of each of us becoming part of a solution. The NJ State legislature is considering a bill (S322/A711) to establish a task force to research, publish a report, and make recommendations regarding institutional racism in NJ. You can learn more about this bill by listening to a webinar (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3v65_hr-iQ) recently sponsored by Episcopal Community Services of New Jersey (ECS-NJ). I found the presentation to be extremely informative and moving. As a result, I will be contacting my state representatives to support this bill.

In the Gospel of John, the Pharisees never opened their hearts and minds to see the blindness inside. I am grateful that Jesus has begun to lift my blindness. I also pray that Jesus is at work in each of us, lifting our blindness, taking us on a journey – a journey to, as the Book of Common Prayer reminds us, where we can all be restored “to unity with God and each other in Christ.