The Right Revered Paul Matthew and his private chapel at ‘Merwick’

by Canon Cynthia McFarland

Archivist and Historiographer of the Diocese of New Jersey

In a longish Anglican life, I’ve had occasion to take part in all manner of services found in all manner of authorised Anglican prayer books. But until recently, I had never participated in a service of deconsecration or, as the Book of Occasional Services* has it, ‘Secularizing a Consecrated Building’.

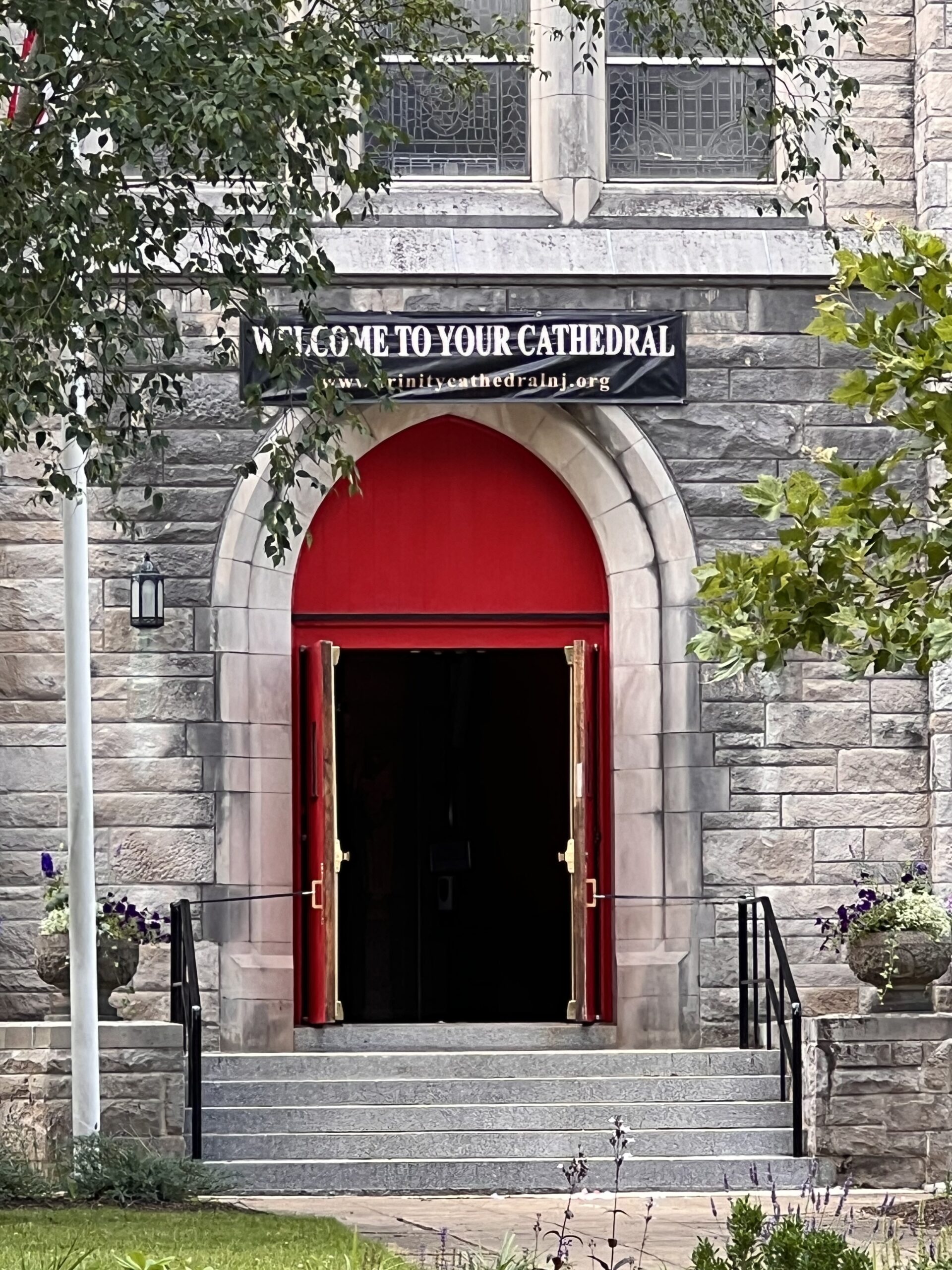

The consecrated building is question is a private chapel in Princeton, New Jersey, part of what was once the Episcopal residence. ‘Merwick’, the name given to the rather vast house built in 1895, served for a brief period as housing for Princeton post-graduate students. In 1918, it was purchased by the Right Reverend Paul Matthews, then Bishop of New Jersey, as his home.

Bishop Matthews was wealthy in his own right, but became more so by his marriage to Elsie Procter, granddaughter of the founder of Procter and Gamble. Elected bishop of the Diocese of New Jersey in 1915, Paul Matthews and his family — four daughters and a son — moved into Merwick after a few uncongenial years in industrial Trenton in the first years of his episcopate.

Alas, Harriet, a bright, lovely, and sweet-natured middle daughter (who seems to have been something of her father’s favourite) died tragically of blood poisoning at Merwick, a few days after her seventeenth birthday in December 1922. Within a year, her father had built and consecrated a private chapel, writing a series of prayers to be used there, all invoking Harriet by name.

The chapel was a lovely one. The reredos, rood, crucifix, and all the carving were fashioned by an admired wood carver in Philadelphia and the twelve windows by a well-known Pennsylvania designer, Valentine d’Ogries. The oratory was well used: In a 1924 journal, the bishop indicates he celebrated Holy Communion there 62 times in a year — and only 29 times in diocesan services.

Although Bishop Matthews resigned as bishop in 1937 at age 70, he remained owner of the house until his death in 1954. After that, Merwick and its nine acres served as a nursing and long-term care home. The chapel was used from time to time for services by visiting Episcopal clergy. But in 2010 the nursing home has moved to new-built quarters beyond Princeton and the University had bought the house and grounds. Merwick and its chapel are to be demolished. The altar, reredos, rood and crucifix, furnishing, fittings and windows will be carefully removed and stored or relocated to churches in the diocese. But all else will come down.

And so it was, before the first strike of the wrecking ball, that 12 people found themselves in the chapel at Merwick, participating in brief service of secularisation led by the ninth Bishop of New Jersey.

What does it mean to ‘secularize’ or deconsecrate? There is disagreement about that and difference amongst the practice of it†. In the Church of England, the deconsecration of a parish church seems to be more a political matter than a theological one. (It requires an Act of Parliament to secularise a parish church, which seems to clearly indicate that in this matter there is a strong Erastian position taken.) The Church of Rome appears to have no particular liturgy, but assumes that when the altar and tabernacle are removed from a church building, there is a de facto deconsecration. The Episcopal Church in the USA is rare in the Anglican Communion in having a formal liturgy.

We who are gathered here know that this building, which has been consecrated and set apart for the ministry of God’s holy Word and Sacraments, will no longer be used in this way, but will be used for other purposes.

To many of you this building has been hallowed by cherished memories, and we know that some will suffer a sense of loss. We pray that they will be comforted by the knowledge that the presence of God is not tied to any place or building.

The Altar will soon be removed and protected from desecration.

It is the intention of the diocese that the congregation which worshiped here will not be deprived of the ministry of Word and Sacrament.

Let the bishop’s Declaration of Secularization now be read.

The fate of churches after they cease being places of prayer and sacrament varies widely, from crumbling, picturesque ruins to urban nightclubs. (Even if a holy space is returned to secular use, the idea of nightclubbers within it still makes us squirm a bit.)

In the case of Merwick Chapel, the very building will vanish, so the enclosed space itself will be gone, the ground to be built over eventually with some other edifice. This seems the best solution, if one has a choice, which one rarely does. The very air contained within the walls, suffused with prayers and petitions, is released to the atmosphere. Whatever was marked and delineated by walls and ceiling — whatever we call ‘sacred space’ — is unbounded and released.

In his poem ‘Church Going’, Philip Larkin comments about a forlorn church building

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete

And that much can never be deconsecrated.

†One can find lively discussions about the whole business on the internet.

Note: This article originally appeared in Anglicans Online on Sunday, 8 May 2011.